The Pole

We made it to South Pole Station. It turns out that getting around this continent necessitates a bit of patience. We spent nearly a week in Christchurch, NZ, waiting for the weather to clear so that we could fly to McMurdo (the primary American station). During that week, we had two boomerang flights in which we took off and flew for ~5 hours down over the Southern Ocean only to get turned around back to New Zealand because the pilots did not feel comfortable landing on the McMurdo Ice Shelf. When the weather finally cleared, we landed in McMurdo and I was greeted by the rest of my science team who had been waiting there for three weeks.

McMurdo is an interesting place. In many ways it reminds me of Kangerlussuaq, the center for US science operations in Greenland. The town sits on the McMurdo Sound, across which are the Royal Society Range which tower to 13000’ from sea level. Being on the coast also means that there is marine wildlife. In the short time that I was there, we saw seals and emperor penguins, but when the icebreaker comes in and breaks the sea ice later in the summer whales, penguins, and seals will surely have a stronger presence. The culture in town in somewhat divided between the contractors and the scientists. They call us ‘beakers’, which, although somewhat condescending, is more endearing than the myriad nicknames I was given in high school.

Finally, on Saturday the 22nd, we flew to the South Pole which will be our home for the next six weeks or so. Using the station as a home base was not our original plan. We had some logistical problems finding a C-130 landing site at Herc Dome meaning that we will be taking day trips in the smaller Twin Otter. Unfortunately, day trips will not be nearly as productive as staying out at Herc Dome for a full month, but the NSF has generously offered us an additional field season (now we will be coming down the next two years) because the logistical problems were out of our control.

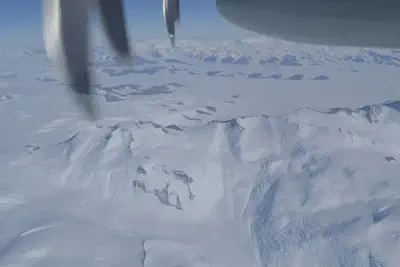

The flight from McMurdo to Pole is over the Transantarctic Mountains. These mountains mark the boundary between East Antarctica, a stable craton, and West Antarctica, an active rift. We commonly consider the East and West Antarctic Ice Sheets as two seperate systems even though the ice is continuous between them. The East Antarctic Ice Sheet is high and cold; it is considered mostly stable. Ice flows down from East Antarctica through the mountains and into the West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) which is lower and relatively warm. The bed of WAIS is below sea level which is the root of its susceptibility for collapse, something that has been very apparent for at least 40 years.

The beauty of the Transantarctic Mountains made it clear to me why ice-sheet landscapes are uniquely attractive. Natural beauty seems to fall into two classifications. The first is the most obvious, being dramatic landscapes such as the Alps or Patagonia. In those settings, sharp contrasts and strong lines highlight features that are striking to our eye. The second is more subtle. The rolling hills of Vermont or even the wide open plains of the Midwest are beautiful because diffusive processes smooth the landscape. These places inspire a feeling of quiet and comfort. Ice-sheet landscapes are unmatched in that they seamlessly coalesce both aspects of natural beauty. Ice flows and diffusively spreads into a smooth surface. Ice far from the mountains is completely flat and white. Only after adjusting one’s perception can the subtle surface slopes be noticed. On the other hand, in mountainous areas nunataks jut straight through the ice, with glacial erosion encouraging steep and dramatic profiles.

Antarctica is stunning, but we are ultimately here for the science. The diversity of interesting science is what makes South Pole Station an exciting place. In the ‘dark sector’ there is the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, which is a 1 km3 network of Cherenkov detectors buried in the ice, and the South Pole Telescope, which measures cosmic microwaves with the objective of gaining insight about the origins of our universe. SuperDARN is a radio antenna, and a part of a worldwide network used to study the aurora. In the ‘clean-air sector’ there are automated weather stations, and UV measurements to study the ozone hole. There are also field projects based out of the station including our own, but also another University of Washington project on ice and firn dynamics upstream of the South Pole Ice Core (SPICE core).

The station feels as if it were designed by a science fiction writer. Perhaps science fiction ideas have been based on facilities such as this one. Eric Steig, one of our team members, made a comment that this is the closest any of us will ever get to space. At first I thought it was a funny comment; however, after getting here I do feel like that, being in a remote and isolated environment in which all the personnel are either directly or indirectly doing work to support scientific objectives. Even maintaining the facility is a tremendous effort. Several tractors are moving snow out from under the station all summer to keep it from being buried.

There are a few quirky aspects of living on station. First, and most obvious, we have 24 hours of daylight. I found this quite entertaining at first, but am getting frustrated to wake up with the feeling that I am late only to realize that it is still 2am. Thorough hand washing on station is a must because viruses circulate quickly. Even with these difficulties, the community here does a lot to keep each other sane. For the first few days after we got here, we were encouraged to relax so that our bodies could properly acclimatize. Since then, we have been working to prepare our science experiments, but have had some down time to explore the station which includes a gym, a green house, a quiet reading room, and the South Pole Store. We even had a nice dinner and there was a foot race ‘around the world’ on Christmas day.