'Working remotely' as a polar field scientist

With an aside on mental health in academia

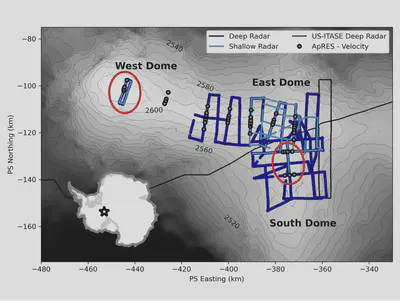

We are wrapping up our fourth* season at Hercules Dome, Antarctica. I use an asterisk because it hasn’t really been the fourth at all. For the first season, in ‘18-’19, we had a 4-person team who was meant to deploy a full field camp for a full month of work on the ground; instead, we spent ~6 weeks at South Pole Station for a handful of day trips commuting back and forth to Hercules Dome. The second season was as expected, ‘19-’20 brought a 7-person team to the field where we did most of the surveying seen in the figure below. The third “season” was not a season at all, Covid halted nearly 100% of Antarctic field work in ‘20-’21. Finally, this current season that is wrapping up now was a small and lightweight team, with only a single scientist on the ground, meant to get in for only a few repeat acquisitions and nothing else. Hercules Dome was originally proposed as a 2-year surveying project and has now been extended to a total of 5 seasons, such is the nature of Antarctic fieldwork during a global pandemic.

I was supposed to be the UW scientist on the ground this season, but I failed the physical qualification examination (PQ) due to mild anxiety/depression. I am not particularly bitter about this. We were able to find a fantastic last-minute replacement, Erika Schreiber of Unavco, who successfully made all of our top priority measurements. Moreover, I was able to spend the holidays with my new fiancée and her family. Having said that, I do want to explain what happened and why I think it is problematic.

In July, I returned from Montana, where I had been riding out the pandemic, to Seattle in order to carry out my PQ. The necessary procedures include dental exams, blood work, as well as a range of other tests depending on the candidate’s age and history within the US Antarctic Program. As some examples, in preparation for my first Greenland deployment they made me get an EKG, and this year the doctor insisted that we do a prostate exam because the language on the document did not make it sufficiently clear that this is only necessary for middle-aged men. Like many others, I have a history of mild anxiety/depression for which I have been prescribed an SSRI in the past. This would not normally be an issue for Antarctic fieldwork, I have travelled to Antarctica carrying this medication before. I have even deployed without the medication at a time when I had elected to stop taking it, my doctor being unconcerned. This year was a bit different though. A flag came up during the mental health check on my PQ (who hasn’t been depressed during Covid??) and I learned that once the flag goes up it is very hard to bring it back down.

Everything being in flux, I saw a new doctor for my PQ this season, one who had no context of my medical history. She was rightfully concerned about my mental health going into a solo field deployment, so she checked the box saying “participant will require further evaluation prior to clearance” since she wanted to start me back on the SSRI for a month before clearing me. Note that this was in July and I was due to deploy in November, so there was time for a secondary evaluation. I believe that my doctor saw me as fit to deploy assuming that I took well to the medication; unfortunately, the medical staff who carry out the PQ paperwork did not see it this way and disqualified me before my doctor could do any further evaluation. There is a procedure to waive the disqualification, but it involves my University signing off on a liability agreement which they were ultimately unwilling to do.

I feel mostly unaffected by this disruption since we were able to find a replacement, and I was well supported by my academic advisor as well as my friends and family. However, this exposed me to inefficiencies within the PQ process which I feel could be more disruptive to others, especially younger students who have not had as many opportunities for fieldwork (note that this is a critical learning experience for many earth scientists). Mental health concerns are rampant among academics, and there should be a clear pathway toward successful participation in field campaigns for anyone who can safely do so. Moreover, the review procedure should rely more heavily on trained mental health professionals. My counselor said that she would be willing to sign off in approval of my deployment, but unfortunately her voice did not carry much weight in the process.

After much back and forth, the decision was made clear that I would not deploy for this season only a few weeks before the scheduled departure. Luckily for us, Erika agreed to fill in as a replacement on this extremely short notice. While she had significant polar experience prior to this season, she had never deployed to Antarctica and obviously didn’t have direct experience at Hercules Dome. Suffice it to say, she got her fill of Zoom calls with me and my advisor. Not only did we need to explain our scientific priorities and instrument procedures, but we also had numerous favors for other field groups which she graciously took on. Luckily she had time for reading and reviewing during her 2-week quarantine in New Zealand.

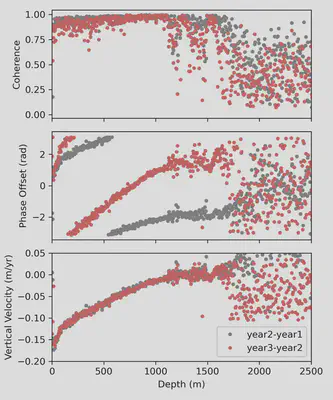

After numerous layovers Erika finally arrived at South Pole Station on December 7th. From there, she would acclimatize before using the Twin Otter as a flight commuter for day trips to Hercules Dome. As is typical for this type of work, she faced weather delays during which she did instrument tests around the South Pole. We were having regular calls and she would send data back to us so that we could check that the instrument was working properly. I could tell with certainty whether she was making the measurement in the same way we had done in the past because she was reoccupying old field sites and if done properly the radar return would be coherent with prior acquisitions. Finally, on December 17th, we had our first true science day at Hercules Dome. She returned with the data shown below which, as you can see in the bottom panel, nicely reproduce a prior result of the vertical velocity structure.

Outside of the scientific priority for the season, a logistical priority was to revisit the cache that we buried in ‘19-’20. Most of what was left there is unimportant, things like food remaining from that season and relatively inexpensive gear such as shovels and sleds. What do need to be recovered are the 30+ drums of fuel we left, most of which is for the airplanes which will now use Hercules Dome as a remote gas station. Erika and the team did not have time to un-dig the cache, so they reflagged it and left the work for next year. Lucky for me, I like digging :)

Hopefully, the upcoming and final season at Hercules Dome will be a full field campaign similar to what we had in ‘19-’20. We need to deploy the field camp in order to fill in the remainder of the survey shown in the top figure. Based partially on new information from the measurements that Erika made this season, we are now focusing wholeheartedly on West Dome as the site at which the ice core will likely be drilled. The ‘22-’23 priority will be to densify our survey around West Dome in order to choose a precise drilling location. Fortunately, the PQ process is renewed on an annual basis, so my disqualification this year has no bearing on future deployments.